Featured Resource

Why Over Half of California School Districts Trust SchoolStatus

Read More >Join Mission: Attendance to reduce chronic absenteeism in 2025-26! >> Learn How <<

Picture yourself sitting down to have a reflecting conversation with a teacher you just observed teaching a lesson. The conversation is going well; the teacher shares that she thought the lesson went okay, basically the way she had planned.

To help the teacher explore her practice more deeply, when the teacher finishes sharing you ask, “So what would you do differently next time?”

Suddenly the teacher’s posture changes.

She sits up straight and diverts her eyes. “What do you mean do differently? I mean, I’m not sure what I’d do differently next time. I thought it went pretty well.” The tone of her voice rises and her speech quickens; something is wrong.

You quickly try to repair the conversation and explain the intention behind your question. The teacher nods but a few moments later asks if you could come back another time, as she just remembered something she has to take care of before her next class of students.

You say, “of course” and that you’ll stop by tomorrow, but the teacher has already moved on. You leave, wondering how your intentions behind the question could have been so badly received.

Crafting questions that invite thinking—while providing psychological safety to the person receiving the question—is a skill that needs attention and intentional practice.

Research says that questioning may be the most frequently used instructional intervention used by teachers, with questions reaching up to 400 a day. As it turns out, questioning is also a main component of almost every coaching model.

If educators, coaches, and instructional leaders know the value of asking questions, why have we have all had those moments when our efforts fall flat?

Through the work of Cognitive Coaching, we continually develop our understanding of this challenge, drawing from both experience and research.

Below are some key ingredients to asking questions in ways that invite and support thinking while creating a safe environment for the response.

These specific structural elements provide the maximum potential to invite thinking, rather than a “gotcha” reactionary response. Rock, in his book Your Brain at Work, cites the work of Mark Beeman in the NeuroLeadership Journal to explain the significance of using questions to help people “focus on their own subtle connections.”

In the above scenario, while the intention of the coach was to explore the teacher’s thinking about the lesson, the use of the word “differently” negatively presupposes that the lesson needs to be changed from the perspective of the coach. Instead of asking a question that might allow the teacher to make their “own subtle connection,” the negative presupposition made the connection for them, possibly leading to the teacher’s defensive response.

Nurturing the growth of educators is critical to enhancing student achievement and success.

Download NowNurturing the growth of educators is critical to enhancing student achievement and success.

Rethinking “What would you do differently next time?”

Let’s rephrase our question using these new tips. It might sound something like this:

“What might (tentative language) be some (tentative language) important parts (plural forms) of the lesson you want to remember (positive presuppositions for reflection) as you plan (positive presupposition for planning) for the next lesson?”

And, of course, the question would be offered in a tone conveying a positive, approachable stance and tone.

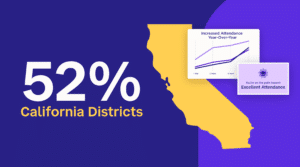

Here are some additional examples of questions with these specific structural elements you might offer in a reflecting conversation after a teacher observation:

Lastly, as you think about using these elements of invitation to coach teachers around their practice, here are a few reminders in posing questions that support thinking:

Next time you sit down for a coaching conversation, revise your questions with these syntactical elements to better match your intention to support your coachee with questions that will allow them to explore their thinking, rather than yours.

Boost is a highly customizable observation and evaluation platform that supports ongoing feedback and growth for teachers and school leaders.

Natalie Irons, a National Board Certified Teacher and Professional Learning Partner with UCLA Center X, supports teachers and school systems as a coach and collaborator. As a Training Associate for Cognitive Coaching, with Thinking Collaborative, she combines a coaching skillset to all her work with Center X.

Carrie Usui Johnson is a National Board Certified Teacher and Director of Professional Development and Partnerships at UCLA Center X, where she supports instructional coaches and school systems as a coach, collaborator and facilitator. As a Training Associate for Adaptive Schools and Agency Trainer for Cognitive Coaching for Thinking Collaborative, she supports individuals and groups in developing self-directedness and resourcefulness.

SchoolStatusSchoolStatus gives educators the clarity and tools they need to get students to class and keep them moving ahead. Through our integrated suite of data-driven products, we help districts spot attendance patterns early, reach families in ways that work for them, and support teacher growth with meaningful feedback. Our solutions include automated attendance interventions, multi-channel family communications in 130+ languages, educator development and coaching, streamlined digital workflows, and engaging school websites. Serving over 22 million students across thousands of districts in all 50 states, SchoolStatus helps teachers and staff see what matters, act with speed, and stay focused on students.

SchoolStatusSchoolStatus gives educators the clarity and tools they need to get students to class and keep them moving ahead. Through our integrated suite of data-driven products, we help districts spot attendance patterns early, reach families in ways that work for them, and support teacher growth with meaningful feedback. Our solutions include automated attendance interventions, multi-channel family communications in 130+ languages, educator development and coaching, streamlined digital workflows, and engaging school websites. Serving over 22 million students across thousands of districts in all 50 states, SchoolStatus helps teachers and staff see what matters, act with speed, and stay focused on students.

News, articles, and tips for meeting your district’s goals—delivered to your inbox.

Ready to learn more about our suite of solutions?