Michael Sonbert encourages ICs and teachers to step out of their comfort zones and participate in role-playing exercises to genuinely impact student growth in the classroom.

In the fall of 2021, I ran training for 30 brand new instructional coaches. Each of them had either just begun coaching teachers in September, or were scheduled to begin just after the new year. The goal was to provide a model for effective communication and, of course, designing and delivering practice.

During the practice portion, coaches stood up and were role-playing a practice they’d designed based on a scenario we provided. I paused them and asked a question of everyone: “Raise your hand if you’re uncomfortable asking another adult to stand up and practice?” Every hand went up. Even in a safe environment, during a role-play where every person was at roughly the same experience and expertise level, every single person was uncomfortable.

Without Practice, You’ll Miss the Mark

This is what’s playing out in most schools. Except instead of having a facilitator (in this scenario, me) to push them to ensure the practice happened, many coaches are simply avoiding it altogether.

Think about that: We work in a field in which making people better is at the heart of the job, and in so many cases, the people charged with doing just this are sending emails with next steps, dropping feedback in mailboxes, and making suggestions in passing. But they’re not practicing.

This is a huge miss. For people to get better at things, they need to see it done well. Then, they need to practice doing it over and over again. Imagine going to a piano lesson and simply talking about playing the piano. Your teacher would make suggestions about how you could play the piano more effectively, and then the lesson would end with you never having seen the teacher play the piano, never putting your fingers on the keys yourself.

This is what plays out in many coaching meetings and the results are often the same: teachers who think that coaching is a waste of time—and who don’t get better as a result—and coaches who feel ineffective and dis-empowered.

Model and Lead by Example

For coaching to be effective, coaches should use data and a digestible framework to land on one teacher action that will improve student outcomes. Then, the coach should provide a model of what that action looks like when done well.

Within that model, they should include the criteria. At Skyrocket we call this, “What makes the thing the thing.” Meaning, it’s not enough to tell a teacher they should praise more students. And it’s not even enough to model praising students for them. The criteria for what makes for good positive praise needs to be shared as well.

Think about these two examples of praise:

- “Nice job”

- “Thank you, Tanya and Jason, for sharing your responses to question three at a level 1”

They’re both positive. They both show appreciation for student work. The second one, however, includes a thank you, student names, and the exact behavior they’re engaging in. While there are dozens of ways praise can look in a school, coaches need to land on the criteria when modeling so teachers can replicate the process after the coaching meeting is over.

In this example, it’s likely this criteria will also include points about voice volume, body position, and so on. For instance, do we step toward the students we’re praising so they’re certain to hear us? Maybe we step away from them so more students hear us and begin working harder as a result?

Once the model is presented, with the criteria clearly named, the coach should role-play the skill multiple times so the teacher can see it done well. Then, the teacher should be asked to practice. What’s important here is that the practice happens as authentically as possible. The teacher should use their “teacher voice” or, if scripting out objectives, they should use their actual lessons.

Bonus: Here’s an example of criteria for giving positive feedback that you can use!

Immediate Feedback is Key

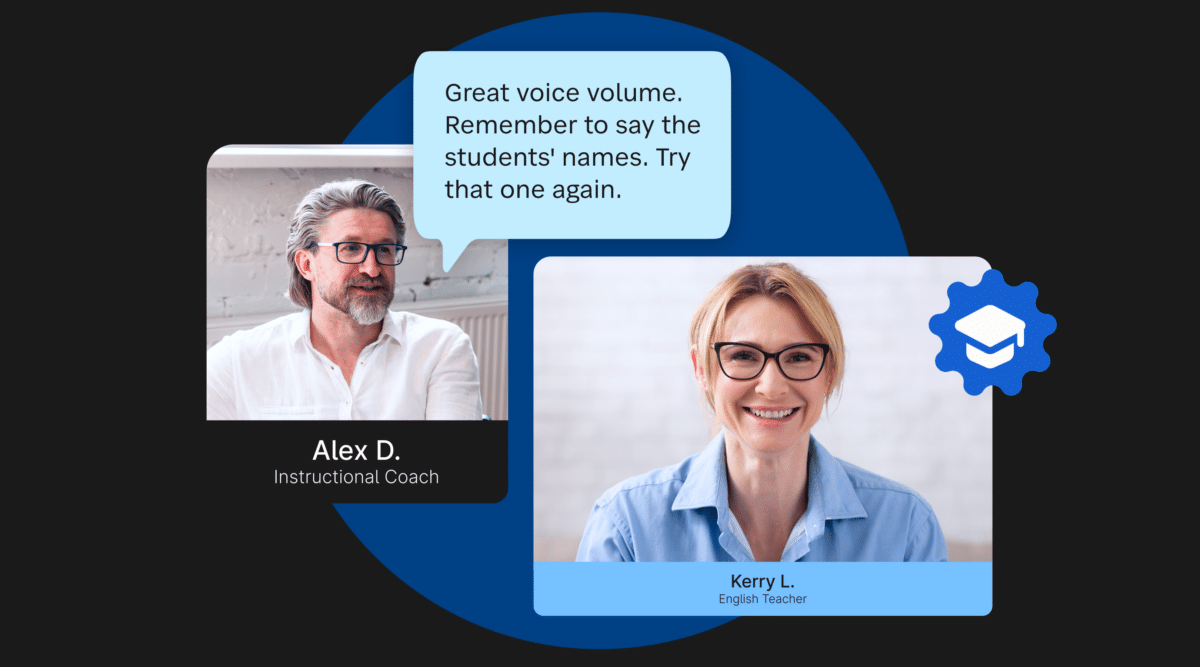

The coach should provide feedback throughout the practice. The feedback should directly relate back to the criteria that was presented.

Think back to my praise example: As the teacher is practicing, the coach could interject and say things like, “Great voice volume. Remember to say the students’ names. Try that one again.”

Like any skill, coaches should push teachers to practice well past the point of them getting one solid rep. That point is the beginning and not the end. Or else, we’re like a basketball coach who tells their players to stop practicing after making one layup. Instead, that’s the time to have them repeat that process over and over so it becomes embedded.

Final Note

It can certainly be uncomfortable to ask another adult to stand up and practice or to sit next to you and script. My suggestion is that you name that discomfort: “Hey, I want us to try something a little different in this session. It might be a little awkward at first, but I’m confident it’ll benefit students. Are you up for it?” Then practice to make the teacher more effective. Once teachers see that your coaching makes a change in their classrooms, the discomfort of practice will disappear.

About Our Guest Blogger

Michael Sonbert is the founder of Skyrocket Education, which specializes in school leader and teacher training. Michael has personally trained leaders and teachers from over 100 cities worldwide, and his Skyrocket frameworks are being used in hundreds of schools internationally. Before he started Skyrocket, Michael was a teacher, instructional coach, and the director of strategic partnerships at Mastery Charter Schools in Philadelphia. He is an autism advocate, a fiction writer, and the lead singer of the bands the Never Enders and Disco Thieves in his spare time. He lives in New York with his wife and three children.

Stay Connected

News, articles, and tips for meeting your district’s goals—delivered to your inbox.